|

Random Notes - A Blog

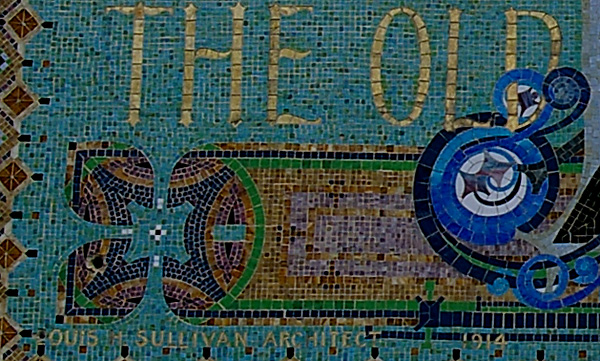

26 July 2008 The teardown mania that has affected residential real estate has also struck schools. Substantial historic buildings in residential neighborhoods are being abandoned at an alarming rate for mega-campuses outside the city limits. Residential preservation is generally small-scale work undertaken by architects and contractors familiar with the special needs of older buildings. Schools, on the other hand, are generally evaluated by big firms more comfortable with the blank slate of a field on the edge of town, and who—surprise—almost always conclude it will be cheaper to build there. Rarely factored in are the increased busing and transportation costs (and consequent impact on student health through less exercise), expenses for infrastructure and extension of police & fire services, and the escalating maintenance costs that will be required by present-day construction, which almost never equals the quality or permanance of historic buildings. And this doesn’t begin to address architectural intangibles. To learn more about saving historic schools, visit the National Trust for Historic Preservation. 5 July 2008 Who could doubt the improvement of this bank building in Louisville, Ohio? Swept away are the large windows and annoyingly permanent brick in favor of machine-like precision and sleek surfaces. The security of your money is now expressed with the modern imagery of the bank as a jail, or at least a walk-in cooler. Sadly, as of this writing, we don’t know whom to thank for this textbook example of architectural evolution. 4 July 2008 While there have been a frightening number of recent tragedies involving older Adler & Sullivan buildings, remarkably, every bank Sullivan ever built is still standing, and still being used for its original purpose…except the one in Newark*. The Home Building Association moved out only thirteen years after the building’s completion, and subsequent occupants included other banks, a butcher shop, jewelry stores and, since 1984, an ice cream parlor. Although the layer of grime on the windows makes the condition of this building appear grim, I suspect that it is fundamentally sound, and could be brought back to life without heroic effort. So, apparently, does Stephen Jones, who graduated from Newark High School in 1983. He paid $225,000 for the building last August, and is working to stabilize it. There is good reason to hope for better care for the Newark Bank. WIth its unusual exterior (entirely clad in terra cotta—unique among Sullivan’s banks) and the remains of the exuberant banking room paint scheme still to be seen above the false ceiling (see Lauren S. Weingarden’s book, Louis H. Sullivan: The Banks), the Home Association Bank building is unlike any other Sullivan bank. The contrast between the terra cotta, which now has the aspect of dirty limestone, and the undimmed polychromatic vigor of the east mosaic is truly striking. This building is as worthy of preservation as any other work from Sullivan’s pencil. Best wishes to Stephen Jones as he undertakes this worthwhile task. * Merchants National Bank in Grinnell, Iowa, is technically no longer used for banking business, that having been moved to the 1976 addition at the rear of Sullivan’s “jewel box”. • • • While the Newark bank may be sad, an Iowa Sullivan bank is definitely unhappy. The People’s Savings Bank building, now home to a branch of Wells Fargo, was filled with water during the unprecedented flooding of Cedar Rapids. I have received no definitive reports, but it is clear that damage could be substantial if water rose to the level of the murals in the upper part of the banking room.

|

| As always, I welcome your comments about this site or any Prairie School building.

John A. Panning, Lake City, Iowa |

|

|

Alabama • Arkansas • Arizona • California • Colorado • Florida • Georgia • Hawaii • Idaho

Illinois • Indiana • Iowa • Kansas • Kentucky • Louisiana • Massachusetts • Michigan

Minnesota • Mississippi • Missouri • Montana • Nebraska • New Jersey • New Mexico

Nevada • New York • North Carolina • North Dakota • Oklahoma • Ohio • Oregon

Pennsylvania • South Carolina • South Dakota • Tennessee • Texas

Utah • Washington • Wisconsin

Australia • Canada • Dominican Republic • Japan • Netherlands • Puerto Rico

• • •

FAQ • Contributors • Random Notes • RIP • Prairie Bookshelf • The Unknowns