|

Random Notes - A Blog

29 October 2008

Such are the times that we live in, that an Iowan sitting at his kitchen table at 10pm can discover the exact address in ten minutes’ time. Google may be Big Brother in the making, but it is the engine that made this discovery possible. Randy’s photos reveal business signs; with these, Google reveals clues. Nothing useful turns up with a search of “Bull Ring” or “Brave Bull”. Tellus Mater, on the building to the right, is actually still in business, but at a location not on State Street. Zorba’s Gyros is not in business, but a Madison history site reveals that it was replaced by Takara, a Japanese restaurant, which is in business and is located at 315 State Street. Here’s where it gets interesting. Madison is one of the cities photographed by Google Maps for its “Street View” feature. With the knowledge of the adjacent building’s address, we can use Google Maps to locate the building, then click on the “Street View” button to see a current photograph of the buildings near that address.

Lo and behold, the building still stands, and in apparently better condition than in 1979. We see that it now houses a bar named “Irish Pub”, which Google reports is at 317 State Street. Mystery solved. And, by the way, La Crosse and Glencoe now have maps. • • • 26 October 2008 • • • 24 October 2008 On 6 January, Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood was damaged in a fire so intense it left adjacent cars “virtually incinerated”. The church was designed by Adler & Sullivan in 1891 as a synagogue for the Kehilath Anshe Ma'ariv (Congregation of the Men of the West); Adler's father, Liebman Adler, was its first rabbi. Located at 3301 South Indiana Avenue, the building was purchased in 1922 by Pilgrim Baptist Church, which, because of the leadership of music director Thomas A. Dorsey, is widely recognized as the birthplace of Gospel music. A survey of the damaged building’s remains revealed that the masonry walls were still structurally sound. On 20 September 2008, a $37 million restoration plan was unveiled, prompting hope that Adler & Sullivan’s masterpiece may be revived. On 24 October, Adler & Sullivan’s 1887 Wirt Dexter Building at 630 South Wabash Avenue was consumed in a five-alarm fire. The remaining shell of the building was deemed too unstable to save, and was subsequently demolished. One of the earliest surviving Adler & Sullivan buildings, the building was described by the Landmarks Division of the City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development as an “irreplaceable link in the chain of work of one of the nation's most important architectural partnerships.” Twelve days later, the George M. Harvey House at 600 West Stratford Place was destroyed in an early morning fire. Completed in 1888, the Harvey House was the last surviving wood-frame structure designed by Adler & Sullivan. A grim roll call. In my entry of two days ago, I failed to mention that not one but three cottages were seriously damaged by Katrina. Sullivan designed (or caused to be designed—pace, FLW) a cottage for himself as well as two for his friend James Charnley in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. When Katrina hit, the Sullivan Cottage was simply swept away—“vaporized”, its owner said. The Charnley Cottage and Guest Cottage were both knocked off their foundations and, although still standing, they remain in perilous condition. • • • 22 October 2008

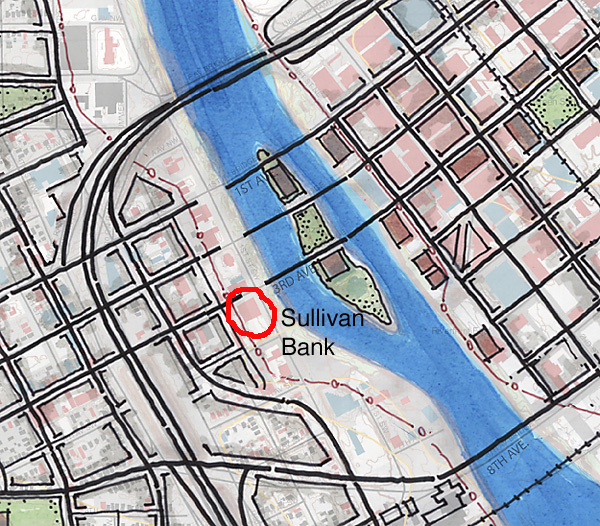

Opposition has arisen to the plan, spearheaded by John & Michelle Schnipkoweit of Cedar Rapids, whose blog details the damage that will be done by the plan and outlines possible alternatives. Speaking on a strictly personal level, it is gut-wrenching to contemplate the calculated loss of another Sullivan building, this one thoughtfully restored under the direction of architect Wilbert Hasbrouck in 1991 and carefully maintained by successive owners Norwest and Wells Fargo. Readers may recall that three Sullivan buildings in Chicago have been damaged or destroyed by fire in 2006, and that the Charnley Cottage, claimed by both Sullivan and Wright, was seriously damaged by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The tribulations of the Cedar Rapids bank and other wrecked Sullivan buildings have been chronicled in the blog of Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin. Unlike involuntary losses by fire or weather, the possible destruction of People’s Savings Bank is entirely premeditated. In its haste to protect against another 500-year flood, it appears that Cedar Rapids is willing to destroy the things that make a city worth saving. • • • 12 October 2008 Thanks to the generosity of five individual owners and the congregation of Redeemer Missionary Baptist Church, over 250 attendees were permitted access to some of the finest of P&E’s Minneapolis work. Almost all owners permitted interior photographs, with the results you see in these pages. The earliest building was built in 1909 for the Stewart Memorial Presbyterian Church, now Redeemer Missionary Baptist Church and the subject of an award-winning restoration. The latest building is the seminal house Purcell built for himself, a product of the Purcell & Elmslie partnership. The remaining residences, the Parker House, the Hineline House, the Owre House, and the Powers House, were designed during the Purcell, Feick & Elmslie days. Although the exterior expressions of the houses are very different, their interiors share striking similarities. All have free-flowing first floor plans, central fireplaces, characteristic art glass, and, for the time, an unconventional treatment of the windows. All have been sympathetically maintained by their owners. One, however, is ready for a new owner: the Hineline House is for sale, with a current asking price of $499,000.00. The most modest of the houses seen, it is nevertheless a very livable gem. This is the place to make an important point. The essence of Prairie School design is not found in casement windows, horizontal trim, bands of windows, geometric art glass, flat roofs, or any one of dozens of other visual traits. Rather, the true essence of the Prairie School residence is found in a modern arrangement of interior space that flows to the exterior. It is space that is organized around the way that modern people of the day lived, and continue to live. Its influence, even though bastardized, is seen in the open plans, cathedral ceilings, fireplaces, and sunken rooms of today’s justifiably loathed McMansions. So don’t be fooled by the drive-by shooting style of photography seen on this site: many buildings pictured here bear only visual or surface characteristics of the Prairie School, and were treated by their creators as just another “style”. Their interiors may well be as conventional as a Victorian house of twenty years previous. While often very interesting, they frequently do not express the most important tenets of Prairie School design. Fortunately, through the efforts of the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota, several hundred people were able to experience the real richness of progressive architecture in the works of Minneapolis’ most important Prairie architects. With the success of this tour, we can hope that other owners will open their houses to future tours. • • • If you’re a member of Facebook, feel free to visit and join the Prairie School Traveler Group. You can meet other like-minded friends, start discussions, and post photos.

|

| As always, I welcome your comments about this site or any Prairie School building.

John A. Panning, Lake City, Iowa |

|

|

Alabama • Arkansas • Arizona • California • Colorado • Florida • Georgia • Hawaii • Idaho

Illinois • Indiana • Iowa • Kansas • Kentucky • Louisiana • Massachusetts • Michigan

Minnesota • Mississippi • Missouri • Montana • Nebraska • New Jersey • New Mexico

Nevada • New York • North Carolina • North Dakota • Oklahoma • Ohio • Oregon

Pennsylvania • South Carolina • South Dakota • Tennessee • Texas

Utah • Washington • Wisconsin

Australia • Canada • Dominican Republic • Japan • Netherlands • Puerto Rico

• • •

FAQ • Contributors • Random Notes • RIP • Prairie Bookshelf • The Unknowns